A study published today in Blood Advances showed that among patients in Denmark who had slow-growing chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) with no symptoms and a low risk for ever needing treatment, those who stopped seeing their doctors for specialised follow-up had fewer hospital visits, fewer infections, and similar survival after three years compared to those who continued to undergo specialised follow-up.

“To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first study of what happens when specialist follow-up for CLL is stopped,” said Carsten Niemann, MD, PhD, chief physician in the department of haematology at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, Denmark, associate professor at the University of Copenhagen, and the study’s senior author. “Our findings show that it’s feasible to discontinue specialised follow-up in patients who have a very low risk of needing CLL treatment and that doing so does not cause these patients any harm.”

Eighty-four percent of the patients showed no signs of CLL progression and were not referred back to a haematology department within three years, Niemann said. Among the 16% of patients who developed signs of CLL progression and were referred for specialist care again, those who needed treatment received it in a timely fashion, he said.

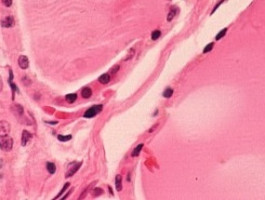

CLL – the most common blood cancer in adults – can be aggressive, meaning it grows quickly, or indolent, meaning it grows very slowly. The average age at diagnosis is 70. While aggressive CLL needs immediate treatment, indolent CLL may remain stable for years without treatment. Studies have shown that up to three in 10 patients with CLL never need treatment. However, these patients often undergo years of specialised follow-up, or “watchful waiting,” including exams and blood tests that may cause them worry and psychological distress, researchers said.

In 2022, Niemann and his colleagues published a validated list of symptoms that identified more than 40% of patients with CLL whose yearly risk of needing treatment is less than two in 100. They conducted the current study to investigate the feasibility of ending specialist follow-up for these very low-risk patients.

The researchers retrieved data from a Danish blood cancer database for all patients diagnosed with, but never treated for, CLL at Rigshospitalet, a large academic medical center in Copenhagen. Patients whose CLL characteristics indicated a high or very high risk that they would eventually need treatment were excluded. Among the 200 eligible patients, the researchers selected 112 who were deemed through a review of their medical records to have a low risk of eventually needing treatment to be discontinued from specialised follow-up. These patients were advised to be vaccinated against pneumonia and influenza and to contact their primary care physicians if they developed fever, chills, night sweats, weight loss, or symptoms of infection. The other 88 patients continued their periodic follow-up visits, including physical exams and blood tests, with their haematologists.

The study’s primary endpoint was three-year overall survival. Secondary endpoints included hospital contacts, the time to developing a first infection, the duration of infections, the three-year rate of re-referral to a haematologist, and the time to needing the first treatment for CLL.

During the three-year follow-up period, the researchers tracked how patients were doing by reviewing their electronic medical records, which documented whether and for how long they were hospitalised, whether they received antibiotics or other medications, and so on.

At three years, overall survival was not significantly different for patients at similar risk levels regardless of whether they had continued or been discontinued from specialised follow-up care. Nineteen patients (16%) in the discontinued group were re-referred to haematologists. Of these, three chose to immediately discontinue follow-up care again and 12 to continue watchful waiting; four received CLL treatment. Fourteen patients in the discontinued group died during the follow-up period, compared with 19 patients in the group that continued specialist follow-up care. Causes of death included infections, other cancers, heart disease, stroke, trauma, and Alzheimer’s disease.

Among 2,811 hospital contacts in total, patients who ended and continued specialised follow-up had 873 (31%) and 1938 (69%) contacts, respectively.

Forty-five percent of the patients who discontinued follow-up care developed infections that were treated with antibiotics, compared with 51% of those who continued follow-up care.

“We have demonstrated that more than half of patients with low to intermediate risk for ever needing CLL treatment may safely be selected to stop specialised follow-up,” said Christian Brieghel, MD, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in haematology at Rigshospitalet and the study’s first author. “They had lower use of hospital and health care resources, a lower frequency of infections, and if they had an infection, they were hospitalised for a shorter time, and their overall survival was comparable to similar patients who continued specialised follow-up care.”

One limitation of the study was that it was not a randomised trial. Rather, the researchers selected patients who met specific low-risk criteria for ever needing CLL treatment to be discontinued from specialist follow-up. In addition, health care in Denmark is universal and free at the point of care; all patients who were discontinued from specialist follow-up were re-referred to a haematologist by their primary care physicians if they developed signs of CLL progression. The study findings might not be generalisable to countries with health care systems based primarily on private health insurance.

Source: American Society of Hematology

The World Cancer Declaration recognises that to make major reductions in premature deaths, innovative education and training opportunities for healthcare workers in all disciplines of cancer control need to improve significantly.

ecancer plays a critical part in improving access to education for medical professionals.

Every day we help doctors, nurses, patients and their advocates to further their knowledge and improve the quality of care. Please make a donation to support our ongoing work.

Thank you for your support.