Medical image analysis using AI has developed rapidly in recent years. Now, one of the largest studies to date has been carried out using AI-assisted image analysis of lymphoma, cancer of the lymphatic system. Researchers at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, have developed a computer model that can successfully find signs of lymph node cancer in 90 percent of cases.

New computer-aided methods for interpreting medical images are being developed for various medical conditions. They can reduce the workload for radiologists, by giving a second opinion or ranking which patients need treatment the fastest.

"An AI-based computer system for interpreting medical images also contributes to increased equality in healthcare by giving patients access to the same expertise and being able to have their images reviewed within a reasonable time, regardless of which hospital they are in. Since an AI system has access to much more information, it also makes it easier in rare diseases where radiologists rarely see images," says Ida Häggström, Associate Professor at the Department of Electrical Engineering at Chalmers.

In close collaboration with Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg and Sahlgrenska University Hospital, she has participated in the development of medical imaging in the field of cancer, as well as in a number of other medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, stroke and osteoporosis.

Large study to track cancer in the lymphatic system

Together with clinically active researchers at, among others, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, Ida Häggström has developed a computer model that was recently presented in The Lancet Digital Health.

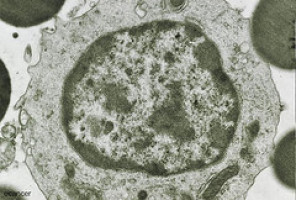

"Based on more than 17,000 images from more than 5,000 lymphoma patients, we have created a learning system in which computers have been trained to find visual signs of cancer in the lymphatic system," says Häggström.

In the study, the researchers examined image archives that stretched back more than ten years. They compared the patients’ final diagnosis with scans from positron emission tomography (PET) and computed tomography (CT) taken before and after treatment. This information was then used to help train the AI computer model to detect signs of lymph node cancer in an image.

Supervised training

The computer model that Ida Häggström has developed is called Lars, Lymphoma Artificial Reader System, and is a so-called deep learning system based on artificial intelligence. It works by inputting an image from positron emission tomography (PET) and analysing this image using the AI model. It is trained to find patterns and features in the image, in order to make the best possible prediction of whether the image is positive or negative, i.e. whether it contains lymphoma or not.

"I have used what is known as supervised training, where images are shown to the computer model, which then assesses whether the patient has lymphoma or not. The model also gets to see the true diagnosis, so if the assessment is wrong, the computer model is adjusted so that it gradually gets better and better at determining the diagnosis,” says Häggström.

In practice, what does it actually mean that the computer model uses artificial intelligence and deep learning to make a diagnosis?

"It's about the fact that we haven't programmed predetermined instructions in the model about what information in the image it should look at, but let it teach itself which image patterns are important in order to get the best predictions possible.

Support for radiologists

Ida Häggström describes the process of teaching the computer to detect, in this case, cancer in the images as time-consuming, and says that it has taken several years to complete the study. One challenge has been to produce such a large amount of image material. It has also been challenging to adapt the computer model so that it can distinguish between cancer and the temporary treatment-specific changes that can be seen in the images after radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

"In the study, we estimated the accuracy of the computer model to be about ninety per cent, and especially in the case of images that are difficult to interpret, it could support radiologists in their assessments.”

However, there is still a great deal of work to be done to validate the computer model if it is to be used in clinical practice.

"We have made the computer code available now so that other researchers can continue to work on the basis of our computer model, but the clinical tests that need to be done are extensive," says Häggström.

The World Cancer Declaration recognises that to make major reductions in premature deaths, innovative education and training opportunities for healthcare workers in all disciplines of cancer control need to improve significantly.

ecancer plays a critical part in improving access to education for medical professionals.

Every day we help doctors, nurses, patients and their advocates to further their knowledge and improve the quality of care. Please make a donation to support our ongoing work.

Thank you for your support.