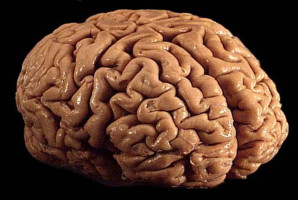

Glioblastoma brain tumours are especially perplexing. Inevitably lethal, the tumours occasionally respond to new immunotherapies after they've grown back, enabling up to 20% of patients to live well beyond predicted survival times.

What causes this effect has long been the pursuit of researchers hoping to harness immunotherapies to extend more lives.

New insights from a team led by Duke's Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumour Center provide potential answers.

The team found that recurring glioblastoma tumours with very few mutations are far more vulnerable to immunotherapies than similar tumours with an abundance of mutations.

The finding, appearing online Jan. 13 in the journal Nature Communications, could serve as a predictive biomarker to help clinicians target immunotherapies to those tumours most likely to respond.

It could also potentially lead to new approaches that create the conditions necessary for immunotherapies to be more effective.

"It's been frustrating that glioblastoma is incurable and we've had limited progress improving survival despite many promising approaches," said senior author David Ashley, M.D., Ph.D., professor in the departments of Neurosurgery, Medicine, Paediatrics and Pathology at Duke University School of Medicine.

"We've had some success with several different immunotherapies, including the poliovirus therapy developed at Duke," Ashley said. "And while it's encouraging that a subset of patients who do well when the therapies are used to treat recurrent tumours, about 80% of patients still die."

Ashley and colleagues performed genomic analyses of recurrent glioblastoma tumours from patients treated at Duke with the poliovirus therapy as well as others who received so-called checkpoint inhibitors, a form of therapy that releases the immune system to attack tumours.

In both treatment groups, patients with recurrent glioblastomas whose tumours had few mutations survived longer than the patients with highly mutated tumours.

This was only true, however, for patients with recurrent tumours, not for patients with newly diagnosed disease who had not yet received treatment.

"This suggests that chemotherapy, which is the standard of care for newly diagnosed glioblastoma, might be altering the inflammatory response in these tumours," Ashley said, adding that chemotherapy could be serving an important role as a primer to trigger an evolution of the inflammation process in recurrent tumours.

Ashley said the finding in glioblastoma could also be relevant to other types of tumours, including kidney and pancreatic cancers, which have similarly shown a correlation between low tumour mutations and improved response to immunotherapies.

Source: DUKE UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER

We are an independent charity and are not backed by a large company or society. We raise every penny ourselves to improve the standards of cancer care through education. You can help us continue our work to address inequalities in cancer care by making a donation.

Any donation, however small, contributes directly towards the costs of creating and sharing free oncology education.

Together we can get better outcomes for patients by tackling global inequalities in access to the results of cancer research.

Thank you for your support.