A research team led by the University of Kent and Goethe-University Frankfurt am Main, has solved an almost 40-year old mystery in leukaemia therapy and the drug nelarabine.

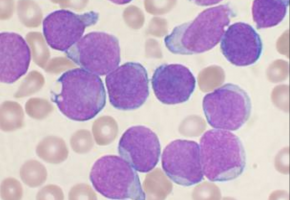

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) is the most common cancer in children.

There are two types of ALL: B-ALL, which resembles B lymphocytes (B-cells); and T-ALL, which resembles T lymphocytes (T-cells).

Since the 1980s, it has been known that the drug nelarabine is effective against T-ALL but not against B-ALL, for reasons unknown.

The new research study now reveals the reason why, and how this can change leukaemia treatments; thanks to the enzyme called SAMHD1.

The research shows that SAMHD1 is present only at low levels in T-ALL, compared to its greater-level of presence in B-ALL cells.

Hence, SAMHD1 protects B-ALL cells, but not T-ALL cells, from the anti-cancer effects of nelarabine.

The findings have crucial practical implications.

There are rare cases of B-ALL in which leukaemia cells display low SAMHD1 levels and thus may benefit from nelarabine treatment.

Additionally, there are also T-ALL cases in which leukaemia cells have high SAMHD1 levels, which are unlikely to react to nelarabine.

Hence, the enzyme SAMHD1 is a biomarker with the potential to tailor nelarabine treatment better to the needs of individual ALL patients.

Dr Mark Wass, an author of the study from the University of Kent, said: 'This work solves an almost 40-year old mystery in leukaemia treatment. The results could immensely impact the effectiveness of particular nelarabine therapy and open other doors of understanding in the effort again this disease.'

Source: University of Kent

The World Cancer Declaration recognises that to make major reductions in premature deaths, innovative education and training opportunities for healthcare workers in all disciplines of cancer control need to improve significantly.

ecancer plays a critical part in improving access to education for medical professionals.

Every day we help doctors, nurses, patients and their advocates to further their knowledge and improve the quality of care. Please make a donation to support our ongoing work.

Thank you for your support.