Sometimes the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

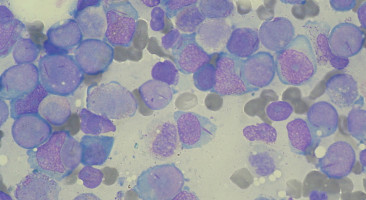

Researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory have discovered that two cell mutations, already harmful alone, enhance one another's effects, contributing to the development of the deadly blood cancer acute myeloid leukaemia (AML).

CSHL Professor Adrian Krainer and his lab, along with Omar Abdel-Wahab at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, detailed how mutations of the genes IDH2 and SRSF2 are unexpected partners-in-crime for causing AML.

Specifically, the presence of the IDH2 mutation enhances the errors caused by the SRSF2 mutation, preventing cells in the bone marrow from maturing into the red and white blood cells an AML patient needs to overcome the disease.

The team is now exploring ways to quickly shut this cooperation down, creating a powerful means to treat blood cancer.

"This all started when we were looking at patient data in The Cancer Genome Atlas and saw that again and again deadly cases of AML had both these mutations," said Abdel-Wahab, a haematologist oncologist.

Prior to this research, the only known similarity between the two mutations was that they are involved in pre-cancerous symptoms.

But in many cases, the cause of the symptoms is not the cause of cancer itself.

"Just because you see a mutation [in a sick patient's cells] doesn't really show that it's directly contributing to the disease," Krainer said.

To determine if the IDH2 and SRSF2 mutations are indeed at work in AML, Abdel-Wahab joined forces with Krainer's lab.

The team detailed their findings in a paper recently published in Nature.

The researchers knew that one of the two mutations in question, the SRSF2 gene, causes errors in a crucial process called RNA splicing.

Splicing converts messages from DNA, called RNA, into readable instructions for a cell.

Errors in this process can result in serious cell malfunction.

Researchers originally did not think splicing defects driven by SRSF2 were tied to AML because DNA tests show the mutations are present in only 1% of AML patients.

The Krainer lab, which specialises in RNA splicing, found that this problem is actually much more common, appearing about 11% of the time in AML patients.

Kuan-Ting Lin, a postdoctoral researcher from Krainer's lab, discovered this by searching for signs of the SRSF2 mutation in RNA.

His search could be likened to dusting for SRSF2's fingerprints within the gene's actual workplace (RNA), instead of simply searching an entire office block (DNA).

"Dr. Lin is very patient, looking at massive amounts of data and picking up distinct patterns and making connections between things that aren't obvious to everyone," Krainer said.

Further experiments from Abdel-Wahab's lab revealed that the severity of the identified SRSF2 splicing errors can be enhanced by the presence of a second mutation, IDH2, resulting in even more defective blood cells.

"So in some ways, these two genes, when defective, are cooperating," Krainer said.

"Now that we do know about this interdependence, we may find points where we can intervene."

Source: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory