Around 22,000 people will be diagnosed this year in the US with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), the second most common type of leukaemia diagnosed in adults and children, and the most aggressive of the leukaemias.

Less than one third of AML patients survive five years beyond diagnosis.

Researchers from Australia's Monash University have discovered a key reason why this disease is so difficult to treat and therefore cure.

The study, led by Associate Professor Ross Dickins from the Australian Centre for Blood Diseases, is published in the prestigious journal Cell Stem Cell.

The paper identifies an important new concept relevant to clinicians involved in the diagnosis and treatment of AML patients.

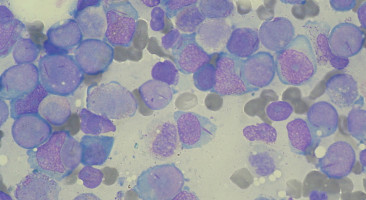

Acute myeloid leukaemia is characterised by an overproduction of immature white blood cells that fail to mature properly.

These leukaemia cells crowd the bone marrow, preventing it from making normal blood cells.

In turn this causes anaemia, infections, and if untreated, death.

Acute myeloid leukaemia remains a significant health problem, with poor outcomes despite chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation.

For decades it has been thought that AML growth is driven by a sub-population of immature cancer cells called 'leukaemia stem cells', which lose their cancerous properties when they mature.

Hence there has been growing international interest in developing therapies aimed at forcing immature cancer cells to 'grow up'.

Using genetically engineered mouse models and human AML cells, Associate Professor Dickins and his Monash-led team have found that maturation of AML cells is not unidirectional as originally thought, but can instead be reversible.

The team, which also includes researchers from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research and several international collaborators, found that even mature AML cells can 'turn back the clock' to become immature again.

This plasticity means that even mature AML cells can make a major contribution to future leukaemia progression and therapy resistance.

The discovery has significant implications for the way that AML is treated, according to Associate Professor Dickins.

"The AML field has traditionally accepted a model where leukaemia maturation is a one-way street," he said.

"By demonstrating reversible leukaemia maturation, our study raises doubts around therapeutic strategies that specifically target just leukaemia stem cells. It highlights the need to eradicate all tumour cells irrespective of maturation state."

These new findings are important because several new drugs that force leukaemia cells to mature have now entered the clinic.

The study by Dickins and colleagues will help clinicians re-shape their thinking to find ways to eradicate mature leukaemia cells along with their immature counterparts.

Source: Monash Unviersity

The World Cancer Declaration recognises that to make major reductions in premature deaths, innovative education and training opportunities for healthcare workers in all disciplines of cancer control need to improve significantly.

ecancer plays a critical part in improving access to education for medical professionals.

Every day we help doctors, nurses, patients and their advocates to further their knowledge and improve the quality of care. Please make a donation to support our ongoing work.

Thank you for your support.