A major new analysis reveals for the first time the likely cause of most cases of childhood leukaemia, following more than a century of controversy about its origins.

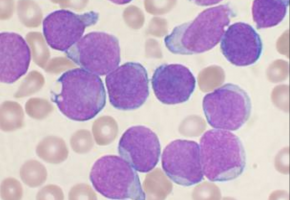

Professor Mel Greaves from The Institute of Cancer Research, London, assessed the most comprehensive body of evidence ever collected on acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) - the most common type of childhood cancer.

His research concludes that the disease is caused through a two-step process of genetic mutation and exposure to infection that means it may be preventable with treatments to stimulate or 'prime' the immune system in infancy.

The first step involves a genetic mutation that occurs before birth in the foetus and predisposes children to leukaemia - but only 1 per cent of children born with this genetic change go on to develop the disease.

The second step is also crucial.

The disease is triggered later, in childhood, by exposure to one or more common infections, but primarily in children who experienced 'clean' childhoods in the first year of life, without much interaction with other infants or older children.

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia is particularly prevalent in advanced, affluent societies and is increasing in incidence at around 1 per cent per year.

Professor Greaves suggests childhood ALL is a paradox of progress in modern societies - with lack of microbial exposure early in life resulting in immune system malfunction.

In a landmark paper published in Nature Reviews Cancer, Professor Greaves compiled more than 30 years of research - his own and from colleagues around the world - into the genetics, cell biology, immunology, epidemiology and animal modelling of childhood leukaemia.

The research in his lab at The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) was largely funded by the charities Bloodwise and The Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund.

Professor Greaves challenged previous reports of possible environmental causes, such as ionising radiation, electricity cables, electromagnetic waves or man-made chemicals - arguing that none are supported by robust evidence as major causes.

Instead, he presented strong evidence for a 'delayed infection' theory for the cause of ALL, in which early infection is beneficial to prime the immune system, but later infection in the absence of earlier priming can trigger leukaemia.

Professor Greaves suggests that childhood leukaemia, in common with type I diabetes, other autoimmune diseases and allergies, might be preventable if a child's immune system is properly 'primed' in the first year of life - potentially sparing children the trauma and life-long consequences of chemotherapy.

His studies of identical twins with ALL showed that two 'hits' or mutations were required.

The first arises in one twin in the womb but produces a population of pre-malignant cells that spread to the other twin via their shared blood supply.

The second mutation arises after birth and is different in the two twins.

Population studies in people together with animal experiments suggest this second genetic 'hit' can be triggered by infection - probably by a range of common viruses and bacteria. In one unique cluster of cases investigated by Professor Greaves and colleagues in Milan, all cases were infected with flu virus.

Researchers also engineered mice with an active leukaemia-initiating gene, and found that when they moved them from an ultra-clean, germ-free environment to one that had common microbes, the mice developed ALL.

Population studies have found that early exposure to infection in infancy such as day care attendance and breast feeding can protect against ALL, most probably by priming the immune system.

This suggests that childhood ALL may be preventable.

Professor Greaves is now investigating whether earlier exposure to harmless 'bugs' could prevent leukaemia in mice - with the possibility that it could be prevented in children through measures to expose them to common but benign microbes.

Professor Greaves emphasises two caveats.

Firstly, while patterns of exposure to common infections appear to be critical, the risk of childhood leukaemia, like that of most common cancers, is also influenced by inherited genetic susceptibility and chance.

Secondly, infection as a cause applies to ALL specifically - other rarer types including infant leukaemia and acute myeloid leukaemia probably have different causal mechanisms.

Professor Mel Greaves, Director of the Centre for Evolution and Cancer at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said "I have spent more than 40 years researching childhood leukaemia, and over that time there has been huge progress in our understanding of its biology and its treatment - so that today around 90 per cent of cases are cured. But it has always struck me that something big was missing, a gap in our knowledge - why or how otherwise healthy children develop leukaemia and whether this cancer is preventable."

"This body of research is a culmination of decades of work, and at last provides a credible explanation for how the major type of childhood leukaemia develops. The research strongly suggests that ALL has a clear biological cause, and is triggered by a variety of infections in predisposed children whose immune systems have not been properly primed. It also busts some persistent myths about the causes of leukaemia, such as the damaging but unsubstantiated claims that the disease is commonly caused by exposure to electro-magnetic waves or pollution."

"I hope this research will have a real impact on the lives of children. The most important implication is that most cases of childhood leukaemia are likely to be preventable. It might be done in the same way that is currently under consideration for autoimmune disease or allergies - perhaps with simple and safe interventions to expose infants to a variety of common and harmless 'bugs'."

Professor Paul Workman, Chief Executive of The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said "This research has been something of a personal, 30-year quest for Professor Mel Greaves - who is one of the UK's most influential and iconic cancer researchers. His work has cut through the myths about childhood leukaemia and for the first time set out a single unified theory for how most cases are caused. It's exciting to think that, in future, childhood leukaemia could become a preventable disease as a result of this work. Preventing childhood leukaemia would have a huge impact on the lives of children and their families in the UK and across the globe."