Whenever an organism is damaged, the cells surrounding the wound receive signals to proliferate more intensely so as to regenerate the injured tissue.

Same goes with cancer -- tumour cells may be all but eliminated by radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy, only to return even more aggressively some time later.

The phenomenon of tumour repopulation is explained by a protein called PAF-R (platelet activating factor receptor), which plays a key role in the process, according to a project by a group of researchers at the University of São Paulo's Biomedical Science Institute (ICB-USP) -- supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) -- headed by principal investigator, Professor Sonia Jancar.

Jancar pointed the doctorate thesis by Ildefonso Alves da Silva-Junior which showed that -- at least for the types of cancer studied by the ICB-USP group -- radiation led to the production of molecules similar to PAF, which activated PAF-R in tumour cells, driving increased expression of PAF-R and tumour cell proliferation.

"So this activation promoted tumour repopulation. Using more sensitive methods, the study also confirmed that when the macrophages (a type of defense cell) present in the tumour microenvironment were treated with PAF-R-blocking drugs, they were reprogrammed to combat the disease more effectively."

The experiments that proved the involvement of PAF-R in tumour repopulation were performed with human oral cancer cells and murine cervical cancer cells, in which radiotherapy is usually preferred.

However, scientists found that large numbers of molecules similar to PAF-R were produced in the cultures shortly after irradiating the cells in a radiotherapy simulation.

"PAF is actually a phospholipid produced mainly in inflammatory and cell death processes," Silva-Junior explained.

The researchers then treated some of the cultured cells with PAF-R-blocking drugs.

Various molecules were tested, including some that were already commercially available but had never been used against cancer.

Analysis performed shortly afterwards showed up one-third more death from radiotherapy among the cells exposed to PAF-R antagonists than among untreated cells.

Another analysis performed nine days later showed a much higher rate of cell proliferation in untreated lines, which multiplied about 1.5 times as much as cells treated with PAF-R antagonists.

"In experiments with tumour cell lines and mice, we found that PAF-R-blocking drugs significantly inhibited tumour growth and repopulation after radiotherapy," Jancar said.

"We therefore suggested associating radiotherapy with antagonists of this receptor as a promising new therapeutic strategy."

Proliferation rate in PAF-R-expressing tumour cells

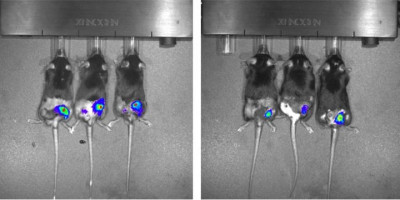

Next they injected under the skin of mice irradiated tumour cells of two lines of genetically modified tumour cells: one that overexpressed PAF-R and other that didn't express PAF-R at all, with the aim of observing the phenomenon of tumour repopulation in vivo.

Researchers measured tumour volume at about 30 days after the cells were injected.

Then, mice were injected with tumour cells and a type of control cell genetically modified to express a light-emitting enzyme that served as a marker inside tumours.

"The control cells were not irradiated, but they were exposed to the same environment and received the signals produced by the tumour to stimulate cell proliferation," Silva-Junior said.

"We used an in vivo imaging system, or IVIS, to measure the proliferation of these luminescent cells and calculate the extent to which irradiation was inducing tumour repopulation."

The results showed that the proliferation rate in the animals injected with irradiated cells that overexpressed PAF-R was 30 times higher than in those injected with non-irradiated cells of the same line.

Some of their results were published in January in Nature's outlet Oncogenesis.

Clinical trials

Sonia Jancar added that the ideal approach would be to return to clinical trials of PAF-R antagonists performed in the 1980s with patients with asthma or pancreatitis.

"For these diseases, the trials were negative, but they could be positive against cancer. I hope our publications alert other researchers in the same field so that they can take this step. Meanwhile, we're evaluating ways of protecting our findings," she said.

To find out whether the results were specific to the tumour cell lines studied to date, the researchers at ICB-USP are now replicating the experiments with ten other kinds of human tumour and performing trials in which PAF-R antagonists are tested in combination with chemotherapy drugs.

The researchers are also testing new kinds of PAF-R inhibitors on the tumour cell lines, including a group of molecules isolated from a marine fungus by Professor Roberto Berlinck and his team at the São Carlos Chemistry Institute in the interior of São Paulo State.

"Several of these molecules have proved to be powerful PAF-R antagonists and capable of inhibiting tumour repopulation," Jancar said. "Although the discovery is important, the road to validation and use in clinical trials is long and requires collaboration among researchers in basic science like us, chemists to synthesise molecules, and clinicians to test them in healthy subjects and in patients."

Source: FAPESP

Photo caption: Cells genetically modified to express a light-emitting enzyme serve as tools to monitor tumour repopulation.

Photo credit: Sonia Jancar / University of São Paulo