Researchers at NYU Langone Medical Center and its Perlmutter Cancer Center have uncovered a critical pathway by which pancreatic cancer cells turn off the immune system charged with attacking them.

The findings appear in a paper published online in Nature Medicine.

The study, conducted in mice and including analyses of human cancers, found very high levels of two proteins – dectin-1 and galectin-9 – in pancreatic tumors.

Their interaction prevented first-responder immune cells, called macrophages, from triggering reactions that kill cancer cells.

Related analyses of human patient data linked elevated levels of galectin-9 to reduced survival in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA), although larger, confirmatory studies are needed, say the authors.

Perlmutter researchers used a mouse model of PDA, a disease that is usually fatal in patients within five years of diagnosis.

They compared mice with pancreatic cancer that made dectin-1 against a group engineered to not make the protein, and determined that the mice without dectin-1 lived longer.

The research team also found that treating mice with an antibody that blocked the galectin-9/dectin-1 interaction dramatically reduced tumour size and increased survival.

“Pancreatic cancer cells are deadly because they program nearby immune cells to permit the tumours to survive and grow,” says study author George Miller, MD, head of the Cancer Immunology Program at Perlmutter and vice chair for research in the Department of Surgery at NYU Langone.

“Our study reveals a previously unknown mechanism that we might be able to block to make tumours ‘visible’ again to attacking immune cells, perhaps in combination with other immunotherapies,” says Miller, also an associate professor in the Department of Cell Biology.

The body’s immune system, which recognises and destroys invading microbes, also recognises tumours as abnormal.

But cancer cells put out signals that help them evade immune response, say the authors.

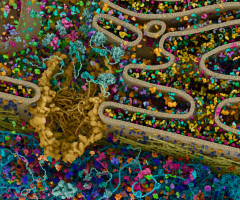

The new NYU Langone study revolves around the ability of immune cells to "decide" which cell types to become based on the type of invader encountered – including macrophages that arrive first at the sites of infection.

Macrophages of the M1 class effectively kill cancer cells, say the authors.

However, if instead macrophages mature into the M2 class they suppress anti-tumor responses.

Pancreatic cancer cells are known to emit signals that shift the lineage of in-rushing macrophages from M1 to immune-suppressing M2.

This effect has been linked in past studies to shorter survival in cancer patients, but how it happens is not entirely understood.

M1 and M2 macrophages each have protein receptors on their surfaces that let them receive signals from their surroundings.

The new study revealed that pancreatic cancer cells not only send signals that make macrophages produce abnormal amounts of dectin-1 surface receptors, but also that make tumour cells themselves express high levels of galectin-9.

Galectin-9 turns on dectin-1, shifting macrophages to the M2 pathway and preventing them from fighting cancer, say the researchers.

When mice bearing pancreatic tumours were injected with an antibody that prevents galectin-9 from docking into dectin-1, they developed M1 macrophages, which sent signals that dramatically increased the number of T cells capable of attacking the cancer cells.

Tumour size in mice injected with the antibody steadily decreased over time, while their survival increased.

While only 25 percent of untreated mice were alive at 55 days, 90 percent of the mice treated with the galectin-9 antibody survived.

Checkpoint inhibitors are an emerging class of immunotherapies that have been approved for the treatment of several cancers.

However, they have been ineffective in clinical trials against pancreatic cancer.

When the study authors treated mice with a combination of antibodies against galectin-9 and the “checkpoint” protein, programmed death receptor 1, or PD1, they found that tumours were less than half the size of those treated with either antibody alone.

This work builds on previous studies by the Miller lab in dissecting previously unknown mechanisms of immune suppression in pancreatic cancer with the goal of developing new immunotherapies.

“Our results have potentially broad implications because macrophages with dectin-1 on their surfaces, and cells expressing galectin-9, infiltrate many cancer types,” says Donnele Daley, MD, a postdoctoral fellow in Miller’s lab, and first author of the current study along with Vishnu Mani, MD. Mani added that “this could be a real game-changer in the treatment of pancreatic cancer patients.”

Source: NYU Langone

We are an independent charity and are not backed by a large company or society. We raise every penny ourselves to improve the standards of cancer care through education. You can help us continue our work to address inequalities in cancer care by making a donation.

Any donation, however small, contributes directly towards the costs of creating and sharing free oncology education.

Together we can get better outcomes for patients by tackling global inequalities in access to the results of cancer research.

Thank you for your support.