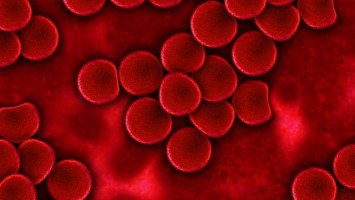

Blood vessels play a critical role in the growth and spread of cancer.

The cells lining the inner wall of blood vessels (endothelial cells) and cancer cells are in close contact to each other and mutually influence each other. Andreas Fischer and his colleagues are studying these interactions.

Fischer, a medical researcher, leads a Helmholtz University Junior Research Group at the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, DKFZ) and the Medical Faculty Mannheim of Heidelberg University.

Fischer and his team had found surprisingly high levels of the activated form of a signalling molecule called Notch in blood vessels of tumours.

In vessel lining cells from lung, breast and bowel tumours, they found significantly higher levels of the activated receptor than they did in the healthy organs.

The researchers observed that the higher the levels of Notch activation were in the tumour endothelium, the more the cancer had already spread and the poorer was the prognosis for the patients.

Activation of the receptor protein Notch by its binding partners is a key communication pathway for signal exchange between neighbouring cells.

Starting from nematodes over insects through to man, Notch regulates the development of organs during embryonic development.

In adults, the signalling protein regulates, among other things, the activity of blood stem cells.

A couple of years ago, cancer researchers were already able to show that aberrant Notch signalling can turn cells cancerous, for example, white blood cells into leukaemia cells.

In the present study, Fischer and colleagues have now demonstrated for the first time that the Notch activity of cells in the tumour microenvironment also has an influence on cancer.

Fischer and his co-workers have demonstrated in mice that the tumour cells themselves are responsible for Notch activation in immediate contact with endothelial cells.

They reprogram the vascular wall cells for their own purposes, thus apparently paving the way for their spread in the body.

The more activated Notch is in the tumour endothelium, the more cancer cells make their way into the bloodstream and the more lung metastases form.

Surprisingly, Notch activation in tumour-bearing mice was not restricted to the blood vessels in the tumour; it also affected the endothelial cells in the lung.

The tumour appears to release signalling substances that prepare the soil for colonisation by its metastases.

As a result of Notch activation, endothelial cells increase their production of a contact molecule called VCAM1.

This protein acts like a snap fastener that enables the cancer cells to attach to the vessel wall and prepare the passage.

In addition, activated Notch makes it easier for cancer cells to get into the bloodstream by making certain structures with sealing function between endothelial cells more permeable.

Finally, activated Notch also causes the endothelial cells to produce chemical messengers that recruit tumour-promoting immune cells into the tumour.

"Taken together, the results show a very clear picture: The tumour cells promote their spread in the body in multiple ways by activating Notch and thus reprogramming endothelial cells for their own purposes," Fischer summed up. "We therefore wanted to find out if we could interrupt this disastrous mechanism."

The scientists blocked Notch in mice using an antibody that is currently being tested in early preclinical trials and thus were able reduce the colonisation of the lung by cancer cells.

A blockade of the contact molecule VCAM1 with an antibody also resulted in less metastases in the lung and lowered the invasion of the tumour by cancer-promoting immune cells.

"Notch is a universal signalling molecule and this makes it difficult to exert therapeutic influence on it without interfering with vital processes," Fischer said. "But a targeted short-time use of blocking antibodies might be a promising approach for suppressing the dangerous spread of tumours. This is what we aim to explore in our further research."

Source: German Cancer Research Center

The World Cancer Declaration recognises that to make major reductions in premature deaths, innovative education and training opportunities for healthcare workers in all disciplines of cancer control need to improve significantly.

ecancer plays a critical part in improving access to education for medical professionals.

Every day we help doctors, nurses, patients and their advocates to further their knowledge and improve the quality of care. Please make a donation to support our ongoing work.

Thank you for your support.